Microcosmos: Elsa Thoresen

Private View

August 24, 6–8 PM

This side of reality

Elsa Thoresen’s late paintings

When you moved on, among frightening constellations and left me

on this side of Jordan you took a half finished homeland with you

– Kjell Espmark, from Skapelsen (The Creation)

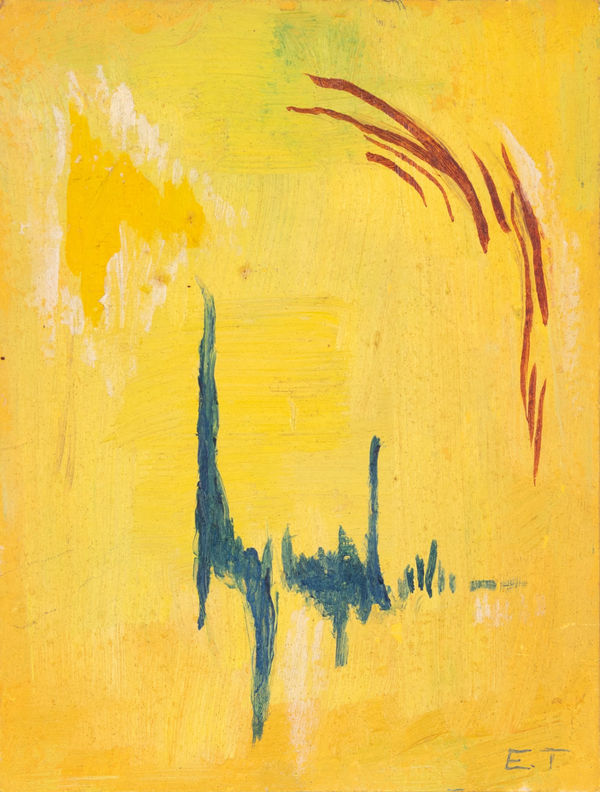

The suite Microcosmos contains 20 paintings created by Elsa Thoresen between 1965 and 1980. The works are painted with oil on panel. The format is strikingly small and they radiate intimacy. The paintings have until now lived a hidden life, found and kept by the artist’s daughter outside of Seattle. They have never before been shown in public.

Elsa Thoresen’s cosmopolitan and multifaceted life took place in many countries and on two continents. The universe she foremost belonged to was the universe of art. She was born on May 1st 1906 in Minnesota, USA and died august 20, 1994 in Seattle. Her artistic identity was on the other hand strongly connected to Europe, where she lived for long periods of time and where she found her original style as an artist.

Thoresen’s father was Norwegian and her mother was American. She grew up in the US and studied at art schools in Oslo and Brussels. In 1934 she met her husband-to-be, the Danish artist Vilhelm Bjerke-Petersen in Oslo. They got married in Copenhagen in 1935. Both became members of the avantgarde movement, who at the time was passionate about Surrealism, not only as an art movement, but as a lifestyle. The circle included among others Wilhelm Freddie, Harry Carlsson, Franciska Clausen and Rita Kernn-Larsen.

Elsa Thoresen and Vilhelm Bjerke-Petersen lived in Denmark until 1943, when the horrors of WWII forced them to escape with their two children to Sweden. In Sweden, Thoresen worked in relation to the Halmstad Group, and exhibited in among other, Stockholm, Karlstad, Örebro and Karlskoga.

Surrealism is often connected to a group of male leaders, such as Salvador Dalí, Max Ernst and Man Ray. But the surrealist movement was also a chance for women to question patriarchal demands and bourgeois values through their art and lifestyle. Among the important women of the movement; Meret Oppenheim, Leonora Carrington and Kay Sage could be found.

Elsa Thoresen personally met many of the stars of the movement. An important sign of recognition is that her works were included in the important Exposition Internationale du Surréalisme in Paris 1938, arranged by the foremost surrealist theoretic, André Breton and the most important poet of the movement, Paul Éluard. In 1947 she was the only woman to be part of the Danish group in the international Surrealist exhibition in Galerie Maeght in Paris.

In Thoresen’s painting from the 1930’s parallels to René Magritte’s figurative Surrealism can be sensed, where everyday objects are dissolved into mental landscapes. In a lighter tone, but in spirit of Magritte, Thoresen makes us question and disbelief the image. The viewer has to sharpen its gaze, flex the muscles of the intellect and be on their guard. One of her most famous paintings of that time, Classical Landscape, shows a large fir tree surrounded by a ring of clouds at its top. At the foot of the tree is a wheel with many pairs of feet. In retrospect the strange composition could be interpreted as a subconscious self-portrait. A tree without roots, constantly on the move. Away from somewhere and towards a mysterious, hard defined “elsewhere”…

After WWII, the figurative elements in Thoresen’s art are dissolved into evermore abstract shapes. The motifs still allude to the organic and nature, but rather more abstract inner landscapes. Throught her art, Elsa Thoresen gazes inwards and steps into another world.

The marriage to Bjerke-Petersen is over in 1953 and Elsa Thoresen moves with her children to Seattle. In November 1953 she marries again, this time to Johnny Gouveia. Life takes a new turn and between 1957–1958 and 1965–1966 she works at the department for lamps and paintings at The Bon Marché, a large department store in Seattle. Is this change in career a practical choice and a need for a steady income? Or is it a sign of disappointment in the way that art is developing? The reasons for Elsa Thoresen’s radical change of life is still to be researched.

But how many knows that she kept painting? Her family and a few more in her inner circles? The distance to the art world doesn’t break her power of creativity. It might even be a blessing. Away from the limelight, that sometimes is a quite an unpleasant place, Thoresen paints, presumably mostly for her own sake. Dreams are grinded in the giant mill of fantasy, to be reshaped into a new, timeless, imaginary world.

This is the way these small jewels of paintings are conceived – colours and shapes in a mysterious dance on remarkably small panels. Although each individual painting is a complete work of art in itself, something magical appears when you view them all together. As if the mysterious element spread from painting to painting using thin threads. The paintings differ, like days in a calendar – they look similar but they can never be repeated. A new mystery awaits around the corner.

The small format forces the eye to come close. So close that you are unsure if you still are outside or inside the painting. The colours shimmer. Mustard yellow. Lilac. Ochre brown. Black green. Intense blue. But they are not mixed! Every paintings have its own tone and palette. “To Plato, colour was a drug as dangerous as poetry. He wanted both out of the republic.” Maggie Nelson reminds us in her book Bluets. Elsa Thoresen’s art could not exist without colour. It carries each image as firmly as the shapes.

The signifying exaggerations of Surrealism have been toned down, in favor of a more abstract and visually poetic language. The suggestion of movement is still there, but the energy is more elegant and feverish here. Sometimes the composition capsizes. The feeling pours away. As if Thoresen got bored with the painting and was on her way into a new image, a new fantasy world. Yet it’s hard to look away. It’s the constant movement, the ability to always find new things in the old that is so unbeatable in these works.

Thoresen found it difficult to relate words to her images. When she exhibited at Färg och Form (Colour and Shapes) in Stockholm, the writer and poet Arthur Lundqvist, in capacity of art critic with a passion for Surrealism, got to choose the titles for her works. The newly discovered paintings from Seattle have no titles to guide the viewer. The gaze is alone with the colours and shapes. But paintings – particularly abstract ones – are never the prisoners of the artist. Every work of art, not just Thoresen’s, is a message in a bottle, waiting to be read. The projections and imaginations of the viewer is as legitimate as the artist’s. From the abstract painting, fantasy can give birth to the most peculiar, worrying or banal events. The magic of the images is an ability to free thoughts and feelings that, without them, might never have appeared.

Joanna Persman, Stockholm, June 2023

Translation by Katarina Sjögren

-

Elsa Thoresen, Untitled, 1964 – 65

Elsa Thoresen, Untitled, 1964 – 65 -

Elsa Thoresen, Untitled, 1964-65

Elsa Thoresen, Untitled, 1964-65 -

Elsa Thoresen, Untitled, 1964 – 65

Elsa Thoresen, Untitled, 1964 – 65 -

Elsa Thoresen, Untitled, ca 1965

Elsa Thoresen, Untitled, ca 1965

-

Elsa Thoresen, Untitled, ca 1968

Elsa Thoresen, Untitled, ca 1968 -

Elsa Thoresen, Untitled, 1968-70

Elsa Thoresen, Untitled, 1968-70 -

Elsa Thoresen, Untitled, 1965-70

Elsa Thoresen, Untitled, 1965-70 -

Elsa Thoresen, Untitled, ca 1965

Elsa Thoresen, Untitled, ca 1965

-

Elsa Thoresen, Untitled, ca 1965

Elsa Thoresen, Untitled, ca 1965 -

Elsa Thoresen, Untitled, 1968-70

Elsa Thoresen, Untitled, 1968-70 -

Elsa Thoresen, Untitled, ca 1970

Elsa Thoresen, Untitled, ca 1970 -

Elsa Thoresen, Untitled, ca 1970

Elsa Thoresen, Untitled, ca 1970